One month in Poland

Palyanytsia* and shades

Today marks exactly one month since we’ve been living in Warsaw.

Outside, the snow piles up to your knees, and inside, it feels like not just your home but also spring has been taken away from you.

There’s a literary device where the weather mirrors the protagonist’s emotional state. Judging by everything, it’s the favorite technique of the lead writer in our horror story.

April 2, 2022. It’s been snowing in Poland for three days now, alternating between blizzards and snowstorms. When we left Kyiv on February 24, it was just as cold and damp.

Some people criticise those who left for posting selfies from cafés, smiling, and wearing red lipstick.

I don’t know. I could put on makeup a hundred times, go to restaurants here, take photos, and even smile, but the feeling of being submerged in a jar of formalin doesn’t go away. It’s as if you’re frozen in an awkward pose, face pressed against glass, holding your breath and blinking mechanically, pretending everything is fine. Because, after all, "you’re safe."

Yes, physically, we are relatively safe.

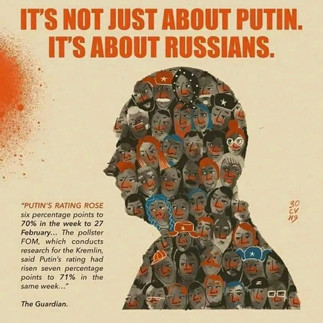

Relatively — because no one knows what might pop into Putin’s head and what could happen tomorrow. The Poles are deeply worried that they’ll be “next,” and I completely understand them. NATO offers no comfort. It’s an instinctive, natural fear.

But this prolonged sense of psychological insecurity is something I’ve never experienced before. Do I need to explain why?

Warsaw is a very beautiful city. As much as I want to resist, I’ve started remembering the routes to our home, meeting neighbors and my sons’ teachers. Cashiers at the nearby stores even know which milk I buy.

Here, I learned that the “language” of drivers — flashing hazard lights to say “thank you” or “sorry”— is universal, and that the middle lane of a road can suddenly become either the left or right lane. So you have to keep your eyes peeled if you don’t want to cut someone off while urgently switching lanes.

Warsaw’s streets are very cozy. It feels like Poles aim to make every square meter of a building useful. Every step, you’ll stumble upon a tiny café with 1-3 tables, where patrons sit closely but maintain a polite distance in their conversations.

Windows sell French fries and coffee, pastries and tea, vegan salads. Nearby, there’s a little bike and scooter shop, a small bank branch, and a tiny beauty salon.

Walk a bit further, and you’ll inevitably find a mini-mecca of fine alcohol and expensive cheeses. You can grab a glass of prosecco and elegantly settle at the single table outside. From a distance, you’d already look like a European. Sitting in dark glasses, legs crossed, basking in the sun. Though more often, you’re frantically scrolling through the news.

Only a sharp-eyed waiter might notice your chronic anxiety in the nervous way you fidget with your phone or your occasional sobs.

Neither physically nor emotionally do I perceive the beauty and love of this city. The mechanism for appreciating beauty is either switched off or destroyed. Time will tell. And this applies to everything — the beauty of the profession, classical music, architecture, the Poles’ quirky traditions, and their rituals.

Accepting so much warmth and care is akin to admitting you need it. For me, that’s equivalent to acknowledging weakness and vulnerability.

Admitting that you:

forgot you’re in Europe, where even moderately serious medications are only sold by prescription;

don’t know the city and wander lost down winding streets despite the confident voice of the GPS;

stall at a huge intersection, can’t start the car, and begin to cry because your Ukrainian license plates feel like flaming scars, revealing your cultural identity to everyone around;

always forget that everything, including pharmacies, is closed on Sundays;

endlessly struggle with parking meters, ATMs, entrances to malls, and stores where robots ask how they can help. “Could you please kill Putin?” I say to one, and it sulks away;

can’t find a decent sports club for your kids, constantly comparing them to the ones back home in Boryspil or Kyiv;

panic when, a month after arriving, your children fall ill because there’s no trusted doctor here, and local ones don’t inspire confidence;

have lost the motivation to look good or feel good.

Our Polish family often send me announcements for activities organized for refugees — from classical music concerts to swimming competitions for children.

Recently, a kind receptionist at a business center asked earnestly about my progress in learning Polish. What could I say? That I don’t have the energy to learn a new language? That starting to learn it feels like admitting I live here? That I don’t want to learn it because I don’t think I’ll need it in the future?

Of course, I said I was trying my best.

Sometimes, I take my kids to events, but I usually feel ashamed because my boys are so noisy and fight a lot. So we leave. And most of the time, I don’t even remember where we were or what we attended.

Warsaw reminds me of an intelligent middle-aged woman dressed in a stylish knit jacket, jeans, and sneakers. In the trunk of her car, there are work documents, a child’s bicycle, and a bottle of water. She has three solutions for every situation and makes decisions quickly and accurately because everything was prepared in advance. Life is organized as it should be; experience has been consolidated, causes and effects studied. Acting is easy and clear.

That’s why today, every Ukrainian, from any Polish building window, can see their national flag and feel the immense support that has become legendary.

Today, I saw the Ukrainian flag on a snowplow.

Lidia, our landlady, brings us groceries from time to time — meat, fruits, vegetables, and sweets for my kids. When she calls to let us know she’s coming, my sons jump on the couch in excitement, already used to her care and hospitality.

At first, I insisted she didn’t need to bring anything, assuring her I could buy almost everything we needed, that we had enough money. But she firmly refused, and I stopped arguing, no matter how hard it was for me.

I saw how important this help was to her.

The biggest paradox is bread.

Lidia always brings an absurd amount of bread — about five loaves, 3-4 baguettes, and 10 rolls. On top of that, there’s usually a pizza. Each time, I don’t know what to do with it since we don’t eat that much bread. And each time, Lidia explains that when she shops around her neighborhood for “my Ukrainian family,” the shopkeepers give her a loaf of fresh bread for us. Because they know what “Palyanytsya” means.

A black turtleneck, dark glasses, and a few extra pounds — that’s been my outfit this past month. Because we’ve left for safety, and yet not entirely.

Because physical safety might come from moving to another country,

but psychological safety is something you must grow within yourself.

April 2, 2022.